Notes

This story was published in Boat Magazine Issue 07: Lima, Peru

“There’s a fee for the guys but not for her,” they grunt, nodding towards me. “And stay as long as you want.”

This story was published in Boat Magazine Issue 07: Lima, Peru

“There’s a fee for the guys but not for her,” they grunt, nodding towards me. “And stay as long as you want.”

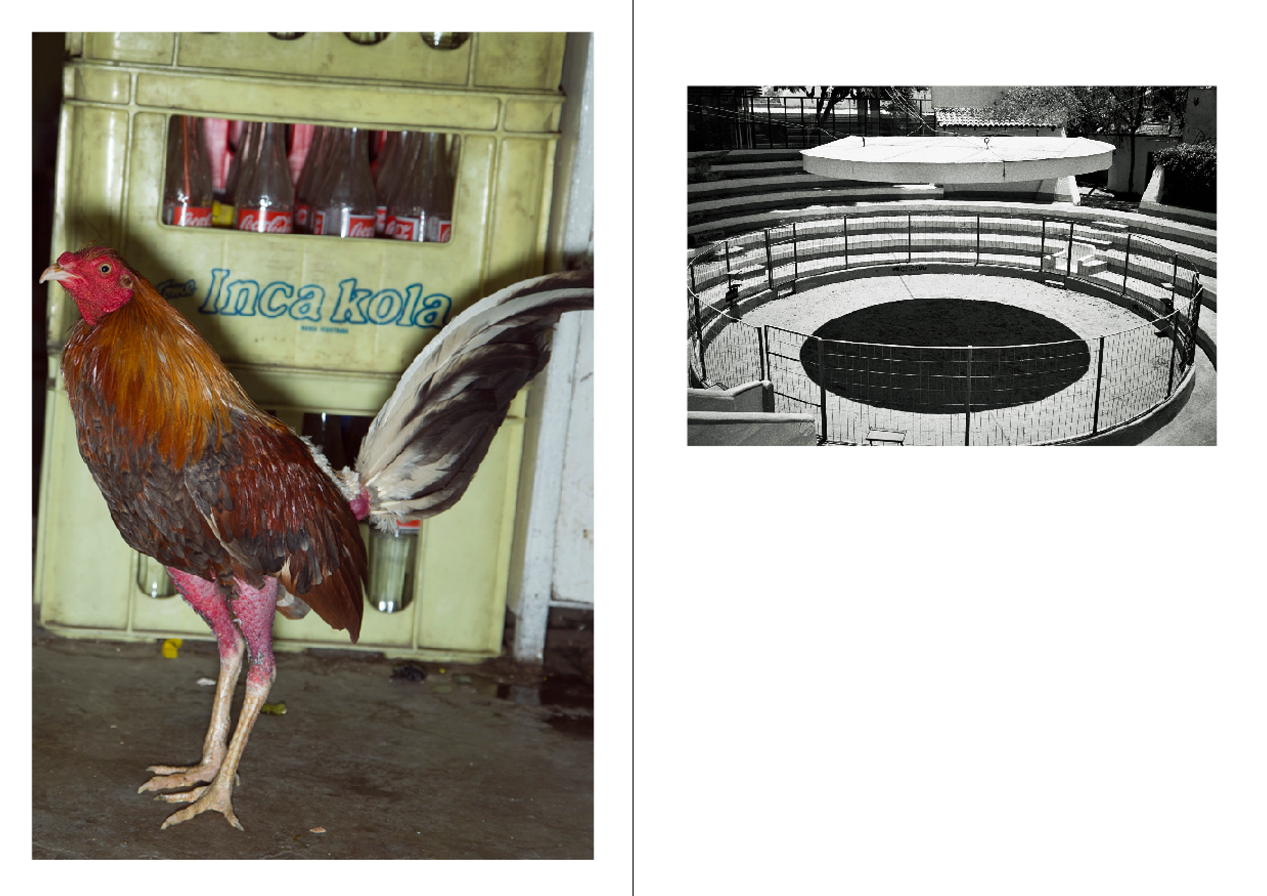

Cockfight

~A journey into Peru’s bloodiest pastime

by Erin Ruffin

We have been driving for almost an hour and all any of us know is that it’s after 11pm, we’re in the bottom-half of Lima and the cockfight we’re meant to be at is “somewhere around here.” The windows are down and over the course of our drive the car has smelled like dust, oily food, honeysuckle, exhaust fumes, salty ocean air, sewage, and then back to dust.

This far south of Lima when the sun goes down the streets go dark apart from every few miles where a neon casino bathes a whole intersection in fluorescent flashing lights like a UFO that has landed to refuel. Combi busses swerve all around us, dodging potholes and picking up passengers anywhere along the roadside. When we get a glimpse of the Pacific Ocean it looks like a mass of solid black glass that’s just swallowed up the rest of the world.

We pull onto a dirt road where stray dogs check out our car and move aside to let us pass. We’ve arrived, but apart from a small opening in a cement wall that allows the sound of shouting men and crowing roosters into the street, you wouldn’t know it. The two local guys who have brought us here talk to the face behind an iron-barred hole in the wall. “There’s a fee for the guys but not for her,” they grunt, nodding towards me. “And stay as long as you want.”

Inside the sound of roosters crowing is like a wall of noise. The ring is set down a level with a box of neon strip-lights hanging six feet above it. Men of all ages, a handful of women and even some kids sit on the slabby cement steps that circle the ring up to the top level where the official score keeper sits, the doctor’s folding table is set up to tend to the birds post-fight, and a makeshift bar sells beer to drink and, unbelievably, hard-boiled eggs to eat.

Despite being totally out of place here, the atmosphere, while inebriated, doesn’t feel threatening; in fact it’s quite welcoming. Within ten minutes I’m talking to Jesus Dueñas, a retired cockfighting judge, who tells me there will be around 80 fights tonight. When a bloodied rooster carried by his owner passes by us, Jesus watches my face for a reaction, “He lost an eye in that fight!” he says. At the doctor’s table the rooster gets antibiotic rubbed into his eye socket and then he’s slipped into a personalized carryall, which looks like a nylon and mesh bowling bag. His owner sits down to watch the next fight, placing the bag with a now-limp rooster inside between his feet.

Three or four owners enter the ring with their birds, the judge chooses two roosters most equal in size and strength, and the others leave. The two chosen roosters pace around pecking at the ground, their owners riling them up while spectators place their bets, shouting out to anyone who will match them.

“Setenta y Cinco! Izquierdo!!” I hear a man shout, placing a $27 bet on the rooster who entered from the left.

“Setenta! Ajiseco!” $24 on the “dry chili” colored rooster.

Bets are not officially recorded but are always honored. When the shouting dies down, the owners pick up their birds for the introduction but not before caressing and whispering into their ear. Then, like boxers touching gloves before the opening bell, the roosters are held out to the other instigating the fight in them and a few vicious pecks before the clock starts running. The two birds are dropped on the ground and both charge directly at one another in an intense and primordial rush of hatred. When their feathered bodies meet, the thrashing, hurtling explosion of the fight turns two separate birds into one angry mess of feathers, a nearly abstract object. Almost beautiful.

There are two types of cockfights in Peru and this is the less gory one, these birds are equipped with their beaks and plastic spikes, historically made of fish bone. The owners clip and file the spurs that grow naturally at the back of the roosters’ legs and then tape longer, sharper plastic spikes over the top. In these fights, called beak fights, there is an 8-minute limit and the bird left standing on his feet (not leaning on a wing or lying down) is the winner, if both are still standing it’s a tie. None of the fights I witnessed resulted in the immediate death of a bird.

The other type of fighting, however, is called ‘spur’ fighting and instead of plastic spikes, a 7-centimeter-long metal blade sharp enough to shave with is placed over one of the bird’s natural spurs. Spur fights do not have a time limit but are instead fought to the death of one bird, which usually happens in seconds.

I don’t know if a swifter end to the fight might be easier to stomach than the slow, fairly torturous fights I’m watching now. At one point, two roosters spar in the air, rising off the ground and throwing each other to opposite sides of the ring. When they get up to standing, their backs are turned to each other and they promptly forget what they’re doing. One looks out at the crowd cocking his head as if confused by his audience, the other pecks the ground looking for food. When one catches wind of the other he immediately jumps on his opponent’s back pecking viciously at his head. The fight ends shortly after that, the rooster on top the winner.

As the night goes on, the roosters keep fighting, the spectators get drunker, more money changes hands and we end up leaving around 2am.

The next morning we’re back in the car headed south again. Our guide is Guillermo Siles whose roosters won best breed in the national championships last year. He’s taking us to see where his roosters are bred, kept, and trained.

Guillermo’s passion for cockfighting started when he was a kid. Now he has breeding and training down to a brutal but fine art: the hens are treated equal to the roosters. Both need aggression, both need “the fight” in them. Sometimes they have good offspring, sometimes they don’t. Only the mad, strong ones are chosen to move on and Guillermo keeps genetic records of all of his fighting cocks, all pedigreed and trained as spur fighters.

When I ask Guillermo if there’s anything he can do to make his birds more aggressive, he says no, that they can only be trained in athleticism, like a boxer works to increase his stamina, strength, and agility. Guillermo, for example, throws his cocks into water forcing them to fight their way back out, but that’s only for physical strength and endurance not for aggression. The mad switch in their tiny brains goes off naturally when they’re near another rooster. He believes the only thing humans have done to turn cockfighting into a sport is to separate the roosters that have a tendency to run from other roosters and to bet money on the outcome, otherwise it’s natural, it’s pure instinct.

“If you research fighting cocks, you’ll go back to Ancient Egypt—3000 years before Christ—you’ll see fighting cocks there. Go back to ancient China, Persia—you’ll see fighting cocks there, too. Why? Because the cock fights. Because he fights. It’s that simple.”

Guillermo believes dinosaurs had that same trait, “which explains why they’re extinct!”

We pull up to a cement wall where a huge door opens to let our car through. We drive along a lush orchard full of ripe fruit trees and tropical flowers through to a barn-sized area where Guillermo’s birds are kept. Rows and rows of clean, spacious pens hold individual roosters and even larger ones line the sides where groups of hens are kept together. In the middle of the compound is a ring used to train the birds. A scale in the corner holds eggs from the hens which Guillermo says have yolks as orange as the sun.

These birds immediately look different. They’re bigger and more regal, stand taller and have huge colorful plumes. Guillermo explains that the difference between these birds and the ones I saw at the fight is that his are bred for spur fighting not beak fighting, and that his breeds are more difficult and expensive to keep. Guillermo’s birds are pedigreed and treated as such, and the ones I saw probably belong to an owner who keeps them in or around his own house like a pet.

“Cockfighting in Peru is for everyone,” he tells me. “Whether you have one rooster in your house or you breed them professionally – it’s the same sport. The guys who have one rooster in their house, they get a good deal, too. The rooster eats their food scraps, the rooster can make them money if they win fights, and then when the rooster dies in a fight, it provides for the family – they eat it! But it’s different, you know. My roosters without a blade would kill those roosters with blades. It’s a different thing.”

When asked about the most memorable moment in his lifetime of cockfighting, Guillermo says it has more to do with the camaraderie between the owners, the community it offers, and the escape it provides to another world of passion and adrenaline. Oh, and Coyote, his cock that won eight fights before he died of old age, the lineage of which is still being maintained and is still winning fights.

Guillermo walks me around the pens pointing out roosters of note. One rooster has the cape of a hen, the neck feathers of his roosters are supposed to be a rusty brown but this guy has white feathers. His stroke of genetic luck has caused his opponents to lie down in the ring submitting to what they think is a female and allowing Guillermo’s rooster to attack.

His most prized bird, Sol de Oro, looks like the meanest in the compound but Guillermo insists on holding him for us. He distracts him through the bars with an iron rod, slowly opens the door, and then Sol de Oro erupts out of the door in a kicking, feathered explosion right into Guillermo’s arms. His body, held under Guillermo’s left arm, kicks and jerks and tries to come loose. All I can see is a blur of feathers punctuated by incredibly sharp claws and the bird’s strong, sharp beak. Guillermo laughs through the struggle, though he looks unsure about who is actually in control.

He finally gets the bird restrained but not without some battle wounds. In the flurry, Sol de Oro pecked Guillermo’s forearm which is now dripping blood. “Oh this is nothing,” Guillermo ensures. He’s been sliced by one of the metal blades before, right down his finger and through the length and depth of his thumbnail.

Peruvian cockfighters will tell you it’s a bigger industry here than soccer with an estimated 1 million people working in it. Guillermo says in Lima, you’re never further than a couple of blocks away from a ring that is used regularly. Sometimes they’re out in the open in the middle of a market, and other times they’re down dark backstreets behind closed doors. In Peru, it’s perfectly legal to fight roosters and after hearing the phrase “cockfighting is in my blood” as many times as I have, it’s easy to believe that the sport is simply one thread in the complex fabric of Peruvian culture, regardless of whether it made me flinch to see a bloodied bird.

In a lot of ways cockfighting does mirror aspects of Peruvian culture and society in general. The fight I attend is an area where $27 would go a long way and yet all those unofficial bets were paid and no questions were asked. That integrity, the dark edge of the sport, the conversation and constant laughter, the feeling that anything could happen at any moment, the community, the pride—it’s all Peruvian.

In his book, The Interpretation of Cultures, anthropologist Clifford Geertz writes:

“What the cockfight says it says in a vocabulary of sentiment - the thrill of risk, the despair of loss, the pleasure of triumph. Yet what it says is not merely that risk is exciting, loss depressing, or triumph gratifying, banal tautologies of affect, but that it is of these emotions, thus exampled, that society is built and individuals put together.”

Jesus Dueñas, the retired judge I met at the fight on the outskirts of town, spent more years judging cockfights than he did in his original career as a high-level security guard to government officials. A friendly, leather-skinned older man who stands on the periphery, Jesus has as much of a place in the arena as the shouting, drinking, betting young men do, he just doesn't stay until the last fight anymore. Still, he was there and he’ll be there, drawn to the fight by some magnetic attraction, until the day he dies.

As Jesus left I asked him what it is about cockfighting that he loves so much. Smiling, he stretched out his arm and swept it around the room as if presenting to me a brand new car. Then he added, putting his hat on, “It’s instinct! The roosters! They’re the ultimate alpha males. If you’re not a rooster, then you’re just a chicken!” And with that he was gone, out of the arena and into the dark and dusty Lima night.

Photographs by

Photographs by