Images 001

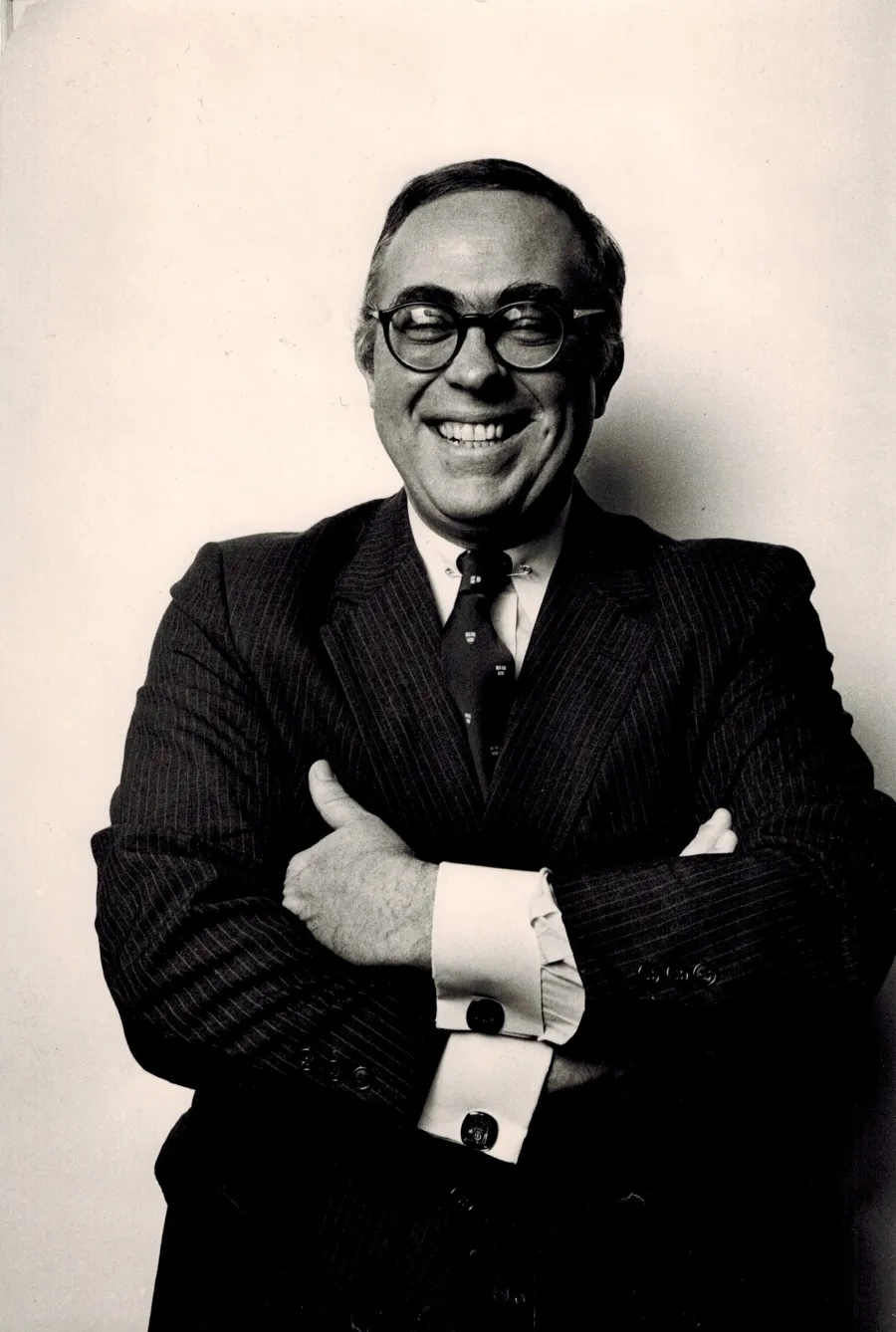

![]() Kevin Starr, 1980, during his time as a San Francisco Examiner columnist

Kevin Starr, 1980, during his time as a San Francisco Examiner columnist

Kevin Starr, 1980, during his time as a San Francisco Examiner columnist

Kevin Starr, 1980, during his time as a San Francisco Examiner columnistNotes

This conversation was published in Boat Magazine Issue 08: Los Angeles

“I think the old clichés about Los Angeles being “brain-dead” or “beautiful but dumb” just don’t work today. They just don’t work.”

-Kevin Starr

This conversation was published in Boat Magazine Issue 08: Los Angeles

“I think the old clichés about Los Angeles being “brain-dead” or “beautiful but dumb” just don’t work today. They just don’t work.”

-Kevin Starr

The Keeper of California

~A conversation with Kevin Star

by Erin Ruffin

Of the last 15 years, I’ve spent six living in New York City, one in Istanbul, five in London and the most recent three here in Los Angeles. As someone who never had an eye on the West Coast, I arrived in the “City of Angels” a little reluctantly, and very naïve. I spent most of my first year here just finding my feet. But every time I felt like I’d started figuring this place out, it would change again.

California, Los Angeles in particular, has always attracted a large number of transplants, and though that number has steadily slowed to match the ever-increasing house prices, my experience moving here is far from unique. I wanted to get some insight into this weird and wonderful place and, more specifically, some advice on navigating it. I could find no one better suited to help me than Mr. Kevin Starr. I was thrilled to spend a couple hours in conversation with him in 2014, just a couple months after moving to Los Angeles, and I treasure some of the wisdom he gave me which I published in the Los Angeles issue of Boat Magazine. Sadly, Mr. Starr passed away this year on January 14, 2017.

Kevin Starr was a decorated American historian, and the author of a multi-volume series of books collectively titled “Americans and the California Dream,” which documents the history of California and analyzes the state’s role in the greater American story. For ten years he served under Arnold Schwarzenegger as the state librarian for California, he has been a professor and lecturer at the state’s top universities, and in his final years served as a member of the faculty at the University of Southern California.

My conversation with him revolves around the nearly 50 years Starr has spent researching, observing, and documenting the state. We talk about the many unique nuances California produces, some of its strengths and weaknesses, and about a new way of seeing Los Angeles that sets it up as one of the best (and possibly one of the most misunderstood) cities in the world. To this day, the capital city of my heart is New York, my first urban love. But, dare I say it, I’m willing to give Los Angeles a chance to win me over and from what I’ve heard, when that happens there’s no going back.

-----

ER: At what point did you decide to focus your career on documenting the history of California? You state in the Preface to “Coast of Dreams” that in the 90’s, at the time of writing the book, California was getting negative press. Was that the case back in the 1960’s? Did you have an agenda to help California shape its reputation?

KS: It was actually much more positive. After my army service finished, some 50 years ago, I had a scholarship to Harvard for a Ph.D. in American literature and studies. Over the course of my studies I had become enormously interested in the various regions of America – how America defines itself regionally – New England with it’s great intellectual traditions, the Middle Atlantic states with their relationship to the Enlightenment, the very distinctive relationship of Virginia to the founding of the republic, and I said to myself: what if we considered California as a regional civilization? What if we considered California on the same level that we consider the south, the Middle Atlantic states, the New England states? And what if we also saw it as an instance of American civilization?

So I started to do my reading and research and I wrote my Ph.D. dissertation, “Aspects of Regional Culture in California at the Turn of the Century,” and I turned it into a book. It was a very successful first book: “Americans and the California Dream.” Then I wrote the second, then the third, then the fourth.. Suddenly I turn around and see myself in my 70s as a grandfather of seven and I’m only up to 1963 [in the chronology of my books on California].

ER: Working on the series, did you feel a great passion for California or did you approach it more from an academic standpoint?

KS: I’m a fourth generation Californian… and I also have a writer’s instinct. That is to say I was responding to the drama of it all and also trying to set up a model or a process or a series of inquiries that would set up a relationship to California as an important dimension of American culture, not just an American afterthought. I remember James Joyce said that he left Ireland “because it was Europe’s afterthought.” Well I don’t agree with Joyce, and likewise California isn’t just an afterthought, it’s not just eccentric – it has very serious American-centric ambitions.

ER: Your books have a very social, journalistic focus.

KS: Well, I think what you’re saying is that I’m a good writer, which is true. But secondly you’re saying that I’m anchored in narrative. I’m looking at those intersection points of personal human experience, social experience, cultural possibilities, economic realities and all those things come together and create very defining moments. My series of books consist of those defining moments – art, architecture, politics, economics, and through those moments I try to suggest the larger California story.

ER: I think that’s a really interesting approach, because traditionally when you hear the label “historian” you don’t think of narrative, though of course that’s the foundation, but we are traditionally taught dates, names, documents and are left to find the narrative in it all ourselves.

KS: If you read a book of mine, at the end of it, you get a sense of social texture. You get a sense of a struggle for cultural definitions that either work or don’t work. They’re either successful for catastrophic but you get a sense of personal dimension and texture – that’s what I’m after.

ER: Absolutely. Take travel writing – if you go back one hundred years it’s done in an incredibly romantic, narrative-driven way, and yet it’s still totally and (sometimes officially) documenting that place at that time. Do you think that side of history- the narrative, social side – is more important to California than to other regions in America? It seems to lend itself very well to the personality of California.

KS: I think in the case, say, of architecture, yes. Our fashion here, we haven’t produced that many great fashion designers. But we’ve produced trends. You take a photograph of people in the 1910s and you can see their sportswear looks very formal. By the 1930s Marlene Dietrich is wearing slacks, and Levi’s are being worn not as work jeans but as leisurewear. Koret of California in the late 30s is producing all kinds of new sportswear and suddenly there’s a new genre of fashion. A lot of trends originated here or were intensified here.

ER: That’s an interesting point when looking at where the “California Dream” sort of sits within the greater American story, it seems to add texture and color more than, say, the middle of the country, where I’m from. I think fashion is an interesting way to illustrate that.

KS: We keep returning to the middle of the country when we are looking for the bedrock American experience. Look at Marilynne Robinson the novelist, the movies “Nebraska” and “August: Osage County.” We turn to California when we want a certain intensification and colorization of that experience. Or quite frankly, of late when we want catastrophic expressions of that experience.

ER: Yes! It’s incredible how often California is portrayed in that light and in that scenario!

KS: Yes, either utopia or dystopia.

ER: Is there anything California took preeminence in early on?

KS: High technology, wine and food culture, modern architecture, and atomic physics – not just for the bomb but also development of nuclear energy - which was not exclusively California but very California-driven. In science, particularly biological sciences, California has more than paced the nation in these issues. Look at venture capital, Silicon Valley… you can see that California is not simply a reflector of American experience but for nearly 200 years now has been a formulator, a pace maker, a paradigm creator.

ER: I’ve lived in New York City, Istanbul, London and when I was moving to Los Angeles, even though I’ve personally experienced a very intellectual side to the city through work I’ve done here, I still fought against the stereotype that LA is “intellectually vacuous.” I know it’s not true! And yet that’s still there.

KS: There are many, many parts to Los Angeles, there are probably 15 or 20 LAs. Where do you live in LA? What kind of activities do you pursue? All these things condition the city. If you take it as a totality it’s certainly not vacuous when it comes to the motion picture industry, it’s not vacuous in terms of universities – UCLA and USC are among the top 20 universities in the nation. It just depends on what circles you live in.

I don’t know what it’s like to just show up. I imagine it’s a very painful thing in many ways to show up in such a city in which all the opportunities are there, but a very high act of personal self-definition is required if you want to lead the intellectual life. You’ve got to find friends that care and you’ve got to condition your own self intellectually.

ER: Do you feel like those stereotypes still exist for LA? Or do you feel that people are able to look at it as the massive city that it is with the many, many pockets of cultures and communities and industries and see that it isn’t as easily classified?

KS: I think the old clichés about Los Angeles being “brain-dead” or “beautiful but dumb” just don’t work today. They just don’t work. However, it doesn’t come together so easily as a city either spatially or any other way as, for instance, New York or London might.

ER: I think it’s interesting that LA doesn’t have the cohesiveness as a city, like London and New York - a very tightly defined identity and creative center, public transportation, walkability - the things that traditionally attract creative types, and yet LA is attracting them again.

KS: Well actually London and LA have a lot in common in terms of their development. London developed moving along the River Thames and gathering different regions to it. So you have very distinctive regions and then in the early 19th century you have Regent Street sort of unifying the whole thing. That’s how LA sort of developed, too, different regions assembled over time into a city. Where New York began in Manhattan with a grid and a highly defined place before reaching out.

ER: Right, New York started with a strong identity and very obvious center. Los Angeles is attracting artists, after maybe a slowing down of that in the past 10 years, it’s picking up again. And yet LA doesn’t have an obvious central hub that many traditional “artist cities” have.

KS: Have you developed a group of people in LA or a relationship with one of the many, many neighborhoods? A group is important. A kind of village within a city.

ER: I wouldn’t say a group, but I have a handful of very close friends who have been here for a few years. Is that a strength that LA has - lots of villages? Or do you see that decentralization as a weakness?

KS: LA demands that. I am a member, for instance, of the USC faculty and that’s my group. I see LA through the lens of that university.

You’re still suffering sticker shock after moving into a totally different environment!

ER: I’d say I’m still in Honeymoon phase. I’m still in awe of every little thing I see here, like a kid in that way. But I know a few people and with my job in publishing/media I have a fairly defined world to explore and join.

KS: You’ll assemble a linkage over time and it’ll be a professional linkage, it’ll be a social linkage and an intellectual one as well. And there are thousands and thousands of those linkages in Los Angeles that make it work.

ER: In the last few years it’s been recommended that young creative people avoid New York City. Patti Smith says it’s priced out all the artists. Would you recommend Los Angeles to them? Is it a good alternative?

KS: I would recommend Los Angeles to an aspiring artist if he or she could afford to live here. Like New York, it's expensive. Also don't move to Los Angeles just on your own. You've got to have some contacts in the city. Otherwise, you'll die of loneliness.

It sounds like you’re already starting to define your own LA to yourself, aren’t you?

ER: I don’t know!

KS: It will be yours. Now don’t forget, this is an invented city, very overnight. You come from London which goes back to Roman times. In 1900 Los Angeles had 100,000 people – it was still a small town. Really just a town! And within the next 30 years it absorbed one million people into it. I call it The Great Gatsby of American cities – a figment of its own imagination.

ER: Is there anything that you worry about for California? Anything that you’re afraid will happen here?

KS: There are all kinds of things that we’re worried about: fiscal probity, public financing, war, the gap between rich and poor, immigration. We’re worried about paying the bills. We were on the verge of going broke a couple years ago. We’re worried about crime.

ER: What about environmental issues?

KS: Environmentally we’re worried and we have a strong history of programs in effect, such as the Sierra Club. Environmentalism is very essential to the Californian formula, to the DNA code of California.

ER: I find it interesting that people don’t seem to be very worried about the drought. In my five years in London (a very wet, rainy place) there were three official hosepipe bans implemented during unseasonably dry periods. The bans went into effect as soon as there was a risk of a drought developing and everyone, for the most part, followed them. I don’t see that happening here.

KS: They haven’t woken up to it, yet. We’ve had all kinds of crises here. We almost ran of out electricity about 15 years ago. If this drought continues, the people will wake up to it, you better believe it.

ER: What would you say is California’s golden era if you had to choose a period?

KS: Well at the risk of sounding sentimental, I think right now. The present. We’re a nation state of 39-40 million people, we have major achievements in our record, we’ve reached a certain maturity as a state. We’re a mosaic of many, many dynamic cultures. We’re a very ecumenical civilization, there’s about 80 languages spoken by the children in the Los Angeles school district. We’ve got major problems, too, but some of the major problems are behind us. For instance, if you had arrived in LA in the early 1960s, you would have said, “I can’t believe the smog! The smog is appalling!” But you don’t say that now. I mean every now and then, you’ll notice it but it’s not at a catastrophic level as it was in the past, so certain problems have been solved.

ER: Do you think Mayor Garcetti’s plan to pedestrianize certain streets around Los Angeles is a good, effective idea? He is hoping to make mini “Main Streets” around LA so that locals will stay local and even walk there instead of drive. Is it feasible?

KS: The paradox behind Mayor Garcetti's plan is that you would have to drive to these places so as to be able to walk there. This is already the situation at Universal City, Third Street Promenade, and The Grove. This is a good solution for Los Angeles. Drive some place so you can experience walking. As I say, it's a paradox.

ER: I am still navigating all of these things that make Los Angeles really unique, certainly driving is a huge change for me. It’s just so totally different from London.

KS: Now take your vulnerability and make it an advantage. In other words, your vulnerability is that you’ve been in LA just for a few weeks, that could be a vulnerability but use it as an advantage. Here you are, you’ve experience two great world cities, New York and London, for periods of time in your life, you’re trying to define this next world city to yourself and you’ve this to consider: this is the city in which one-third of the air traffic over the US at any one time is either coming, going, controlled by or reporting into Los Angeles. This is a city that’s an American capital, the capital of the American Southwest, an Asia Pacific Capital. What’s going on here as you define this to yourself? It’s a city where every type of person, every culture on the planet is represented and it seems to be working. It’s a city that was invented yesterday, more or less, and you’re coming from a city that goes back to the Roman times. So you can have a notion of your defining yourself to this.